Some things your sociologist never told you (Part I)

Someone will always win, and someone will always lose

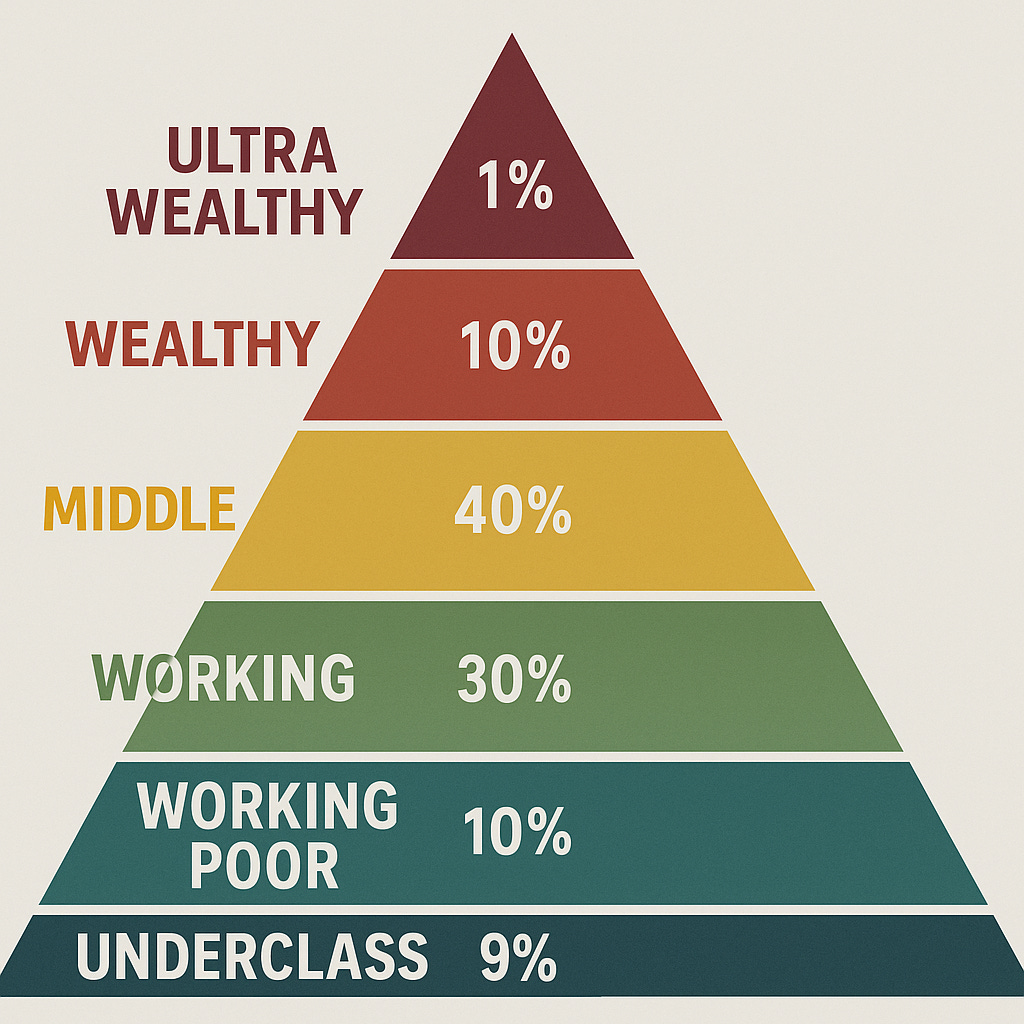

A core insight from sociologists is that societies are stratified. I don’t know if they are still in vogue, but at one time, entire courses were devoted to social stratification and what it means for society. Usually, though, it is a unit within a course. However it is taught, at some point, an image like the one below is used to represent American social stratification.

We all want to be at or near the top. But not all of us are or can be. The way our capitalist system works, regardless of their in-born or cultivated abilities, some people are always going to be on the bottom.

A major element of capitalism is that people compete in markets—labor market, consumer market, housing market, and so on. It’s a competition where people win and lose. This is so axiomatic to the whole enterprise, until attempts at rigging the system are sanctioned. What is an anti-trust law if not an attempt to prevent businesses from rigging the game and not competing fairly? What is an anti-discriminatory law if not an attempt to make the labor market fair for all? Winners and losers are integral to the system.

Understanding that society can be represented as a stratified system has many applications for how we understand the world. Here are two.

The (un)deserving poor and (un)deserving rich

First, people who happen to end up in these bottom rungs don’t necessarily deserve to be there. Their inability to get into a top university could be a function of the number of people applying to those universities and the competition being fierce. Their inability to acquire the two strongest indicators of middle class—a well-paying job and a home in the right neighborhood—could be because they happen to be seeking these things during a tight labor or housing market. The working-class graduate of community college living in a less desirable part of town may not be there because they are less skilled or talented—just less lucky. Less luck in who their parents were. Less luck in when they applied to colleges, what they decided to major in, and so on.

We can do this in reverse. The graduate of Ivy League U, working at a Fortune 500 company, is not there necessarily because they are more talented or hardworking. They may have simply been more fortunate.

I should say it is not that the wealthy person isn’t working hard. This is an argument for understanding the sociological reasons for why one person’s hard work has netted more success than another who put just as much time into their life and career. Your neighborhood sociologist is firmly in the middle class, and whatever talents I may have, I would be foolish to assume I ended up with tenure at a university because of only my talents and hard work. I was just...lucky.

Downstream effects

Second, the downstream effects of occupying these bottom rungs are also inevitable. We can link many “social dysfunctions” to occupying the lower rungs in a social stratification system. I’d say the three categories these dysfunctions fall into are crime, health, and education.

This is all a matter of percentages and probabilities, mind you. People who are wealthy commit crime. A few hours watching the ID channel will illustrate this. They also don’t all go off to top schools. Conversely, not everyone who is poor stays that way or ends up dropping out of school.

With respect to crime, one doesn’t need to take a criminology class to know that crime and poverty are linked. People with lower incomes are more likely to be both criminals and victims—especially in the highest poverty neighborhoods. This relationship is more complex than I wish to go into here, but the relationship has been consistent, even as crime rates have gone down.

Poor health is also a downstream effect. People occupying the lower rungs are more likely to have preventable conditions and diseases like high blood pressure and diabetes. I am from South Carolina, one state in what has been called the diabetes belt. This is a territory of nearly 650 counties across 15 states, primarily in southern Appalachia. Residents throughout this region have a higher likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes. Several relatives in my family—all working class or poor—are struggling with this disease. People on the lower rungs also struggle more with addiction. I can go back to my home state of South Carolina, where drug busts making the news are a common occurrence—especially opioids like fentanyl.

And then there is education. People occupying the bottom rungs—or more specifically their children—are less likely to complete college. At this point, it is nearly impossible for them to compete in the education market and earn slots in top universities or top graduate programs should they finish their undergraduate degree.

At this point, I anticipate someone thinking to themselves as they read: “But people make choices… they had a choice to take drugs or drop out of school or not put in the time needed to get that promotion. It is about personal responsibility and accountability.”

Eh.

It’s like the choice I had as a teen during the summer. I could choose between working in a tobacco warehouse or sitting on my back porch and watching the pile of sunflower seed shells accumulate as I spit them out. Meanwhile, across town and up the stratification ladder, another teen had different choices—working in a relative’s office as a gopher, taking a coding class, going on a summer trip for cultural enrichment.

I am sure two recent college graduates from similarly ranked institutions, with the same degree and GPA, also make “choices.” One, from a working-class home, “chooses” to stay in the area—they have college loans, no startup funds from their parents, and they need to help their loved ones with whatever job they can find, while another “chooses” to accept the best position available wherever it is, knowing their parents will front them their first month’s rent and deposit.

OK, I am putting "choice" and "choose" in quotes too much. You get it—I find the notion of choice to be problematic at best. So yes, we all make…choices. And so if one wishes to see stratification as the consequences of choices, I cannot necessarily object to it.

What does it all mean?

The above is the accepted knowledge within my discipline. It is “the facts” or “the truth” if one wants to look at it that way. I tend to avoid those kinds of terms, as they suggest a kind of permanence and certainty that is never warranted in science. I prefer "accepted knowledge at this time," but admittedly that is a bit clunky—especially for a newsletter. So, these are “the facts.”

At this point, what you do with these facts is up to you and the ideologies you ascribe to (we all have them). But proper education should never be about rote memorization of facts. This is especially true in a sociology class, where concepts have direct and immediate implications in the world. And so, if I were in a classroom teaching this, I would profess, as it were, and demonstrate how I would apply these ideas filtered through my own allegiances and interests. I see two implications:

Don’t get too full of yourself, and don’t get too down on yourself. I mentioned above how I was lucky to have earned a doctorate, a career I enjoy and have had some success in, and a home in a pretty decent neighborhood. I italicized “luck” and “earned” as I think both are needed here. Yes, I did indeed do the work necessary for these things. But I carry with me a healthy sense of my good fortune for having been in the right places at the right times. Conversely, if someone reading this is not where they want to be, despite getting up every day and grinding, it might just be chance and happenstance that has you where you are. Don’t get too down on yourself.

It is immoral for a capitalist society to not have strong safety nets. This is a direct consequence of the understanding that losing is baked into the system. I do not think in terms of deserving and undeserving poor (or rich, for that matter). I know that regardless of the distribution of talents and work ethic in a society, some people will inevitably end up on the bottom rungs. In this sense, a social safety net is not “charity” any more than it is a form of “charity” when a fire department puts out a blaze at someone’s home.

These two conclusions are based on my particular morals and political ideology. Someone else—maybe someone with an ideology centered on the supremacy of the individual (the great man approach)—will likely reject the first conclusion. Elon Musk fully deserves his billions. That homeless woman simply made bad choices; that’s it. Similarly, the second conclusion may be rejected if someone ascribes to a free-market libertarian ideology where all services are privatized. Through the lens of that ideology, something like Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF) and the fire department are seen as unnecessary!

That is what makes sociology such a fun and challenging discipline, and why you need to read even more things your sociologist never told you!